PANS and PANDAS—acronyms for Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections—have become a point of confusion, frustration, and polarization in the medical world. Parents see life-altering changes in their children after seemingly benign infections. But many physicians remain skeptical, if not outright dismissive. Why?

The answer isn’t just about lack of evidence. It’s about belief systems, cognitive dissonance, and the biological cost of challenging established paradigms.

The Biology of Belief in Medicine

Most doctors are trained to view psychiatric symptoms through one of two lenses:

- Situational trauma or stress

- Neurotransmitter imbalances

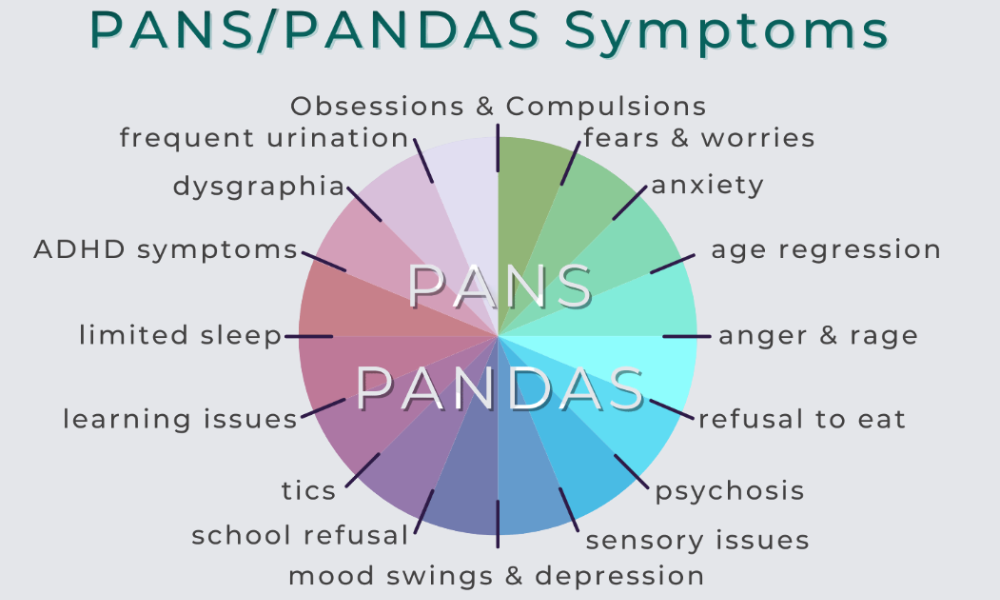

The treatment? Therapy and lifelong psychiatric medications. Mental health is seen as separate from infections, inflammation, and immune dysfunction. When you introduce the idea that sudden-onset OCD, tics, rage episodes, or regression could be caused by an infection triggering an autoimmune or autoinflammatory process, you aren’t just proposing a new diagnosis. You’re challenging the entire framework used to understand mental illness.

Acknowledging PANS/PANDAS requires clinicians to question their training, rethink their assumptions, and accept that they may have missed something critical in previous patients. This is not a simple cognitive shift. It triggers cognitive dissonance—a stressful internal conflict between new evidence and old beliefs. And the natural human response to that discomfort is often cognitive closure: rejecting the new idea to preserve internal coherence.

The real friction comes not from a lack of proof, but from the need to rethink old frameworks.

Why the Narrow Definition of PANDAS Backfired

One of the major obstacles to medical acceptance is the overly narrow framing of PANDAS as strep-triggered OCD and tics in children. A landmark 2004 study found no consistent association between group A strep infections and neuropsychiatric symptom flares in children with Tourette's syndrome (Kurlan et al., 2004). This study, and others like it, gave the broader medical community permission to dismiss the idea as unproven or overblown.

But here’s the problem: strep is not the root cause. It’s a trigger—one of many possible triggers.

In my experience, patients who react to infections with psychiatric symptoms have one thing in common: a dysregulated immune system primed by upstream root cause factors. These include:

- Biotoxin-producing pathogens (Borrelia, Bartonella, Babesia)

- Mycotoxin exposure (from mold illness)

- Excessive limbic system activation (amygdala hypervigilance)

Without these underlying imbalances, most people are able to clear infections like strep or Mycoplasma pneumoniae without their immune system launching an attack on their own brain.

So when we define PANS/PANDAS too narrowly, we not only exclude the majority of cases—we give doctors a reason to write off the diagnosis entirely.

Academic Support Does Exist

Despite the controversy, legitimate institutions do recognize and treat PANS/PANDAS:

- Stanford University’s PANS Clinic within the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

- The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has published and funded research on PANS

- Numerous peer-reviewed studies have shown elevated antineuronal antibodies and markers of inflammation in affected children

But widespread clinical adoption lags behind academic recognition.

Why? Because accepting PANS/PANDAS as real means rethinking the medical separation between brain and body, mind and microbe.

Reframing the Conversation

PANS/PANDAS, like Chronic Lyme, needs a paradigm shift.

Just as Lyme disease isn’t just about Borrelia burgdorferi, PANS/PANDAS isn’t just about strep. It’s a syndrome born of immune dysregulation and microbial triggers. And when we understand it that way, the path to healing becomes clearer:

- Identify and reduce immune-disrupting microbes

- Address environmental toxins like mold

- Calm the overactive stress response system

This upstream approach doesn’t negate the role of strep or Mycoplasma. It just puts them in context.

Final Thoughts

If you or your child has been dismissed, doubted, or gaslit while searching for answers, know this: skepticism doesn’t equal truth. Sometimes it just reflects discomfort with a new reality.

Healing from PANS/PANDAS means treating more than just infections. It means healing the immune system, reducing inflammation, and restoring communication between the brain and body.

And sometimes, it means protecting your belief in what you know is real—even if others aren’t ready to see it yet.

Scientific References:

- Kurlan, R., Johnson, D., Kaplan, E. L., Tourette Syndrome Study Group. (2004). Streptococcal infection and exacerbations of childhood tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A prospective blinded cohort study. Pediatrics, 113(6), e578–e585. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.e578

- Chang, K., Frankovich, J., Cooperstock, M., Cunningham, M. W., Latimer, M. E., Murphy, T. K., ... & Swedo, S. E. (2015). Clinical evaluation of youth with Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS): Recommendations from the 2013 PANS Consensus Conference. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2014.0061

- Murphy, T. K., Patel, P. D., McGuire, J. F., Kennel, A., Mutch, P. J., Parker-Athill, E. C., & Storch, E. A. (2015). Research Review: The role of infection and immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders: A review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12320

- Agalliu, D., Garcia, F., & Elias, S. (2021). Autoimmune encephalitides and autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders in children: The case of PANS and PANDAS. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 33(6), 656–663. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001059

- Lewin, A. B., Storch, E. A., Murphy, T. K., Geffken, G. R., & Goodman, W. K. (2011). A pilot study of intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 21(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2010.0120

- Hesselmark, E., & Bejerot, S. (2017). Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) in Sweden: An observational study of diagnoses and treatment characteristics. BMJ Open, 7(6), e015630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015630

- Frankovich, J., Thienemann, M., Rana, S., & Chang, K. (2015). Five youth with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome of differing etiologies. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2014.0073